This was a popular saying of my Great Grandmother ~ Miriam Bridelia Soljak

.

She’s noted in NZ history books as a teacher,

political activist,

feminist

and journalist.

She also knew all the words to all the Gilbert and Sullivan musicals

and raised 7 children.

Miriam was born in Thames in New Zealand in 1879,

the sixth of 8 children from Irish born Mathew Cummings and Scottish born Annie Cunningham.

Tall and angular with an intense gaze,

Miriam excelled in Thames and New Plymouth High Schools and became a teacher at 19.

Her first post was to Taumarere Native school in Northland

and then to Pakaru where she boarded with a Maori family.

Miriam became deeply interested in the Maori Culture and was soon fluent in Te Reo.

She met her husband Petar Soljak up north when she was riding side saddle and a strap broke,

causing her to get off her horse.

Her friend told her to hurry up and get back on because the Austrians were coming.

The Austrians were actually a group of Dalmatians including Petar Soljak.

This is when they first met and they were married in 1908.

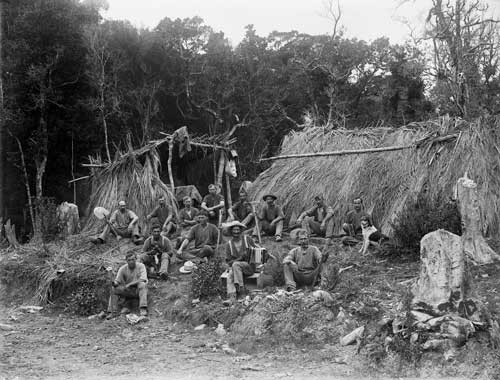

Petar had recently migrated from Dalmatia to escape conscription into the army of the hated Austrian Empire.

He had little education, his English was imperfect

but he was practical and could turn his hand to anything.

They loved each other and had a bustling household

but Miriam found that by marrying an Austrian immigrant,

She too had become an enemy alien.

She was forced to register with the Police and her activities and possessions were restricted.

The hardworking Petar dug ditches,

built stone fences,

transported flax to the rope works

and worked as a gum digger

to provide for his fast growing family,

but they struggled financially and were constantly moving.

His children remember him as a loving father,

and a great story teller – who was very knowledgeable about Yugoslavian History.

But his search for work often took him away for long periods of time

leaving Miriam to run the house and 7 children.

She resumed her teaching in Pakaru where her work was so valued by the Maori community,

they provided day care for her young family.

She maintained friendships with her students from Northland all her Life.

Miriam’s daughter Connie Purdue remembers her mother refusing to obey traffic lights.

“Just look at them dear,” she would say to the oncoming traffic.

In her writings some of which I have inherited,

amongst the many letters to the editor, speeches, film scripts and journals

is a story titled ‘A Maori Heroine’.

It’s the true story about the heroic journey of Hene Pouri

who was the only Maori woman at Gate Pah in the Waikato,

fighting alongside the warriors in the trenches she had helped build.

.

But that is another story.

.

Indeed I’m discovering so much history delving into Miriam’s writing,

it’s overwhelming and I have decided to concentrate on the law change Miriam helped bring about :

that of losing your NZ nationality.

During the First World War,

NZ women

who married foreigners

automatically lost their NZ nationality,

taking their husband’s instead.

Because of her enemy alien status,

Miriam was refused a bed in a maternity home,

when giving birth to her 7th child, Paul.

This was the last straw and it spurred her to political activism.

She joined the Auckland Women’s Political League in 1920

when the family moved to St Mary’s Bay Road in Ponsonby.

Emily Gibson who was an Active worker for the Labour movement,

lived across the road,

and the two became life long friends.

Miriam tall and erect and Emily; tiny and white haired walked to many a branch meeting in Newton and Hobson Streets.

The Women’s Political league morphed into the Auckland Women’s branch of the Labour Party

and it was on this platform the determined Mrs Soljak succeeded in putting ‘independent nationality

firmly on the agenda.

7 years later, Peter Fraser, a Labour Politician,

presented Miriam with a private member’s bill he had put forward;

allowing NZ women to adopt their husband’s or retain their own nationality,

when marrying a foreigner.

This legislation was only upheld in NZ and Miriam had to travel on an endorsed passport

when she took her cause to England in 1936.

The photo of my great grandmother is upon her arrival to a May Day parade in Hyde Park, London

in 1937.

She looks victorious.

Now 57 years old and traveling alone from NZ by steamship,

she had presented the independent nationality issue to the ‘British Commonwealth League.

A fluent speaker and skilled writer,

Miriam explained to this influential Women’s organization the plight of a NZ woman,

losing their own Nationality when marrying a foreigner.

At this conference,

she was accorded the honour of moving the annual resolution reaffirming the right of a married woman

to her own independent personal nationality on the same terms as a man.

But it wasn’t until 1946,

41 years after marrying Petar Soljak,

that Miriam’s nationality was finally restored.

With the end of the 2nd World War

came the demise of the British nationality and Status of Aliens Act.

She passed away in 1971,

a New Zealander through and through,

she asserted her nationality and championed the cause for Urban Maori and working class women fearlessly and with total commitment.

As a teenager and anti Vietnam war protester in the late ‘60’s,

I remember seeing my great grandmother on a soap box in Albert Park speaking on disarmament and World Peace.

She was in her late 80’s.

In the last notes to her family Miriam says,

.

“I wish to express my love to all the members of the family

for affection and regard shown to me

and trust they will remember not my errors and failings as a mother,

the basis of which they were never capable of understanding.”

.

It wasn’t until 1977

that a NZ woman could pass her NZ citizenship to her foreign born husband and children.

Bernard, Miriam’s sixth child, known as Barney,

has a connection with Waiheke Island.

He transported concrete by barge

for the building of the Stony Batter Cannon Emplacement in 1942.

What was it like having such a staunch activist as a great grandmother?

We always found her kind although her Christmas presents were a bit different.

My sisters and I were curious when her gifts arrived,

firmly tied up in brown paper and string.

4 children’s books, one for each of us.

We would study the pictures of hundreds of children working,

studying, singing and exercising with the ever present face of Mao Tse Tung beaming down like a benevolent father.

Then one Christmas,

the best package came with an LP and book and an exercise chart.

My sisters and I copied all the exercises and marched around our sunny bedroom in Havelock North,

reciting ‘Ho chey yo’, etc.

It wasn’t until years later

we discovered we had been practicing the Communist army exercise routines,

taught to children in China.

We also learned at a young age

that if you resisted or objected to anything

our father would say

’You’re just like Miriam’,

yes, it is true she was not that popular among the kiwi blokes of the 1950’s.

Little were they to know then,

that thanks to the life long struggle of women like my Great Grandmother,

unfair laws towards New Zealand women would eventually be changed forever.

.

~ Katy Soljak

Waiheke Island, New Zealand

.