On Sept. 1st, 1859, the most ferocious solar storm in recorded history engulfed our planet. It was “the Carrington Event,” named after British scientist Richard Carrington, who witnessed the flare that started it. The storm rocked Earth’s magnetic field, sparked auroras over Cuba, the Bahamas and Hawaii, set fire to telegraph stations, and wrote itself into history books as the Biggest. Solar. Storm. Ever.

Dr.Tony Phillips

Space Weather

Wed, 30 Sep 2020

But, sometimes, what you read in history books is wrong.

“The Carrington Event was not unique,” says Hisashi Hayakawa of Japan’s Nagoya University, whose recent study of solar storms has uncovered other events of comparable intensity. “While the Carrington Event has long been considered a once‐in‐a‐century catastrophe, historical observations warn us that this may be something that occurs much more frequently.”

To generations of space weather forecasters who learned in school that the Carrington Event was one of a kind, these are unsettling thoughts. Modern technology is far more vulnerable to solar storms than 19th-century telegraphs. Think about GPS, the internet, and transcontinental power grids that can carry geomagnetic storm surges from coast to coast in a matter of minutes. A modern-day Carrington Event could cause widespread power outages along with disruptions to navigation, air travel, banking, and all forms of digital communication.

Many previous studies of solar superstorms leaned heavily on Western Hemisphere accounts, omitting data from the Eastern Hemisphere. This skewed perceptions of the Carrington Event, highlighting its importance while causing other superstorms to be overlooked.

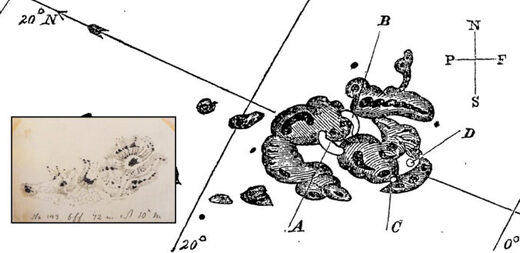

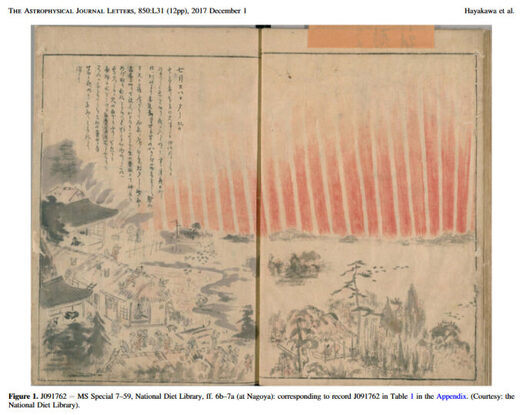

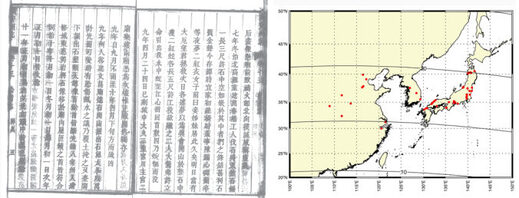

A good example is the great storm of mid-September 1770, when extremely bright red auroras blanketed Japan and parts of China. Captain Cook himself saw the display from near Timor Island, south of Indonesia. Hayakawa and colleagues recently found drawings of the instigating sunspot, and it is twice the size of the Carrington sunspot group. Paintings, diary entries, and other newfound records, especially from China, depict some of the lowest-latitude auroras ever, spread over a period of 9 days.

An eyewitness sketch of red auroras over Japan in mid-September 1770.[Ref]

“We conclude that the 1770 magnetic storm was comparable to the Carrington Event, at least in terms of auroral visibility,” wrote Hayakawa and colleagues in a 2017 Astrophysical Journal Letter. Moreover, “the duration of the storm activity was much longer than usual.”

Comment: The event may have been even stronger than the Carrington Event but because the use of electricity was still in its infancy it’s difficult to compare the disruption the event had on the functioning of daily human life.

Hayakawa’s team has delved into the history of other storms as well, examining Japanese diaries, Chinese and Korean government records, archives of the Russian Central Observatory, and log-books from ships at sea-all helping to form a more complete picture of events.

They found that superstorms in February 1872 and May 1921 were also comparable to the Carrington Event, with similar magnetic amplitudes and widespread auroras. Two more storms are nipping at Carrington’s heels: The Quebec Blackout of March 13, 1989, and an unnamed storm on Sept. 25, 1909, were only a factor of ~2 less intense. (Check Table 1 of Hayakawa et al‘s 2019 paper for details.)

[Ref]

Contextualizing the Carrington Event has become a busy niche in space weather research. One team led by Jeff Love of the USGS recently confirmed the near equality of Carrington to the May 1921 superstorm. And Hayakawa’s team has just unearthed new records of extreme auroras in South America.

Are we overdue for another Carrington Event? Maybe. In fact, we might have just missed one.

In July 2012, NASA and European spacecraft watched an extreme solar storm erupt from the sun and narrowly miss Earth. “If it had hit, we would still be picking up the pieces,” announced Daniel Baker of the University of Colorado at a NOAA Space Weather Workshop 2 years later. “It might have been stronger than the Carrington Event itself.”

History books, let the re-write begin.

Get your copy from our Online Store or your local book and magazine retailer

Australian Retail Locations » Uncensored Publications Limited

New Zealand Retail Locations » Uncensored Publications Limited

As censorship heats up and free thought becomes an increasingly rare commodity, we appeal to our readers to support our efforts to reach people with information now being censored elsewhere. In the last few years, Uncensored has itself been censored, removed from the shelves of two of our biggest NZ retailers – Countdown Supermarkets and Whitcoulls Bookstores – accounting for 74% of our total NZ sales.

You can help keep the Free Press alive by subscribing and/or gifting a subscription to your friends and relatives.