Prefer facts to Political Correctness? Try this:

Paul Craig Roberts

paulcraigroberts.org

Tue, 12 Mar 2019

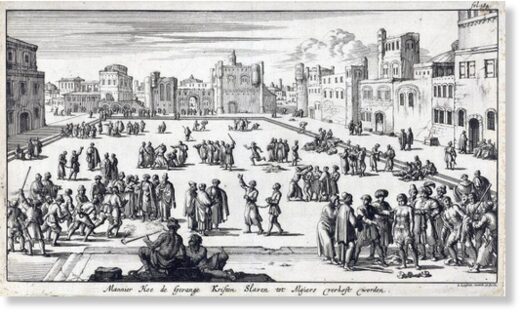

Christian prisoners are sold as slaves on a square in Algiers

Things that used to be true before political correctness set in:

Before sending ignorant hate mail, consider these Wikipedia entries:

“The Barbary slave trade refers to the slave markets that were lucrative and vast on the Barbary Coast of North Africa, which included the Ottoman provinces of Algeria, Tunisia and Tripolitania and the independent sultanate of Morocco, between the 16th and middle of the 18th century. The Ottoman provinces in North Africa were nominally under Ottoman suzerainty, but in reality they were mostly autonomous. The North African slave markets were part of the Berber slave trade.

“Ohio State University history Professor Robert Davis describes the White Slave Trade as minimized by most modern historians in his book Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast and Italy, 1500-1800. Davis estimates that 1 million to 1.25 million Europeans were enslaved in North Africa, from the beginning of the 16th century to the middle of the 18th, by slave traders from Tunis, Algiers, and Tripoli alone (these numbers do not include the European people who were enslaved by Morocco and by other raiders and traders of the Mediterranean Sea coast),[3] and roughly 700 Americans were held captive in this region as slaves between 1785 and 1815.[4]

“From bases on the Barbary coast, North Africa, the Barbary pirates raided ships traveling through the Mediterranean and along the northern and western coasts of Africa, plundering their cargo and enslaving the people they captured. From at least 1500, the pirates also conducted raids along seaside towns of Italy, Spain, France, England, the Netherlands and as far away as Iceland, capturing men, women and children. On some occasions, settlements such as Baltimore, Ireland were abandoned following the raid, only being resettled many years later. Between 1609 and 1616, England alone had 466 merchant ships lost to Barbary pirates.[8]

“While Barbary corsairs looted the cargo of ships they captured, their primary goal was to capture non-Muslim people for sale as slaves or for ransom. Those who had family or friends who might ransom them were held captive, the most famous of these was the author Miguel de Cervantes, who was held for almost five years. Others were sold into various types of servitude. Captives who converted to Islam were generally freed, since enslavement of Muslims was prohibited; but this meant that they could never return to their native countries.[9][10]

“Sixteenth- and 17th-century customs statistics suggest that Istanbul’s additional slave import from the Black Sea may have totaled around 2.5 million from 1450 to 1700.[11] The markets declined after the loss of the Barbary Wars and finally ended in the 1800s, after a US Navy expedition under Commodore Edward Preble engaging gunboats and fortifications in Tripoli, 1804 and later when after a British diplomatic mission led to some confused orders and a massacre; British and Dutch ships delivered a punishing nine-hour bombardment of Algiers leading to an acceptance of terms. It ended with the French conquest of Algeria (1830-1847).

“Perpetrated largely on Europeans, and within in-land routes to indigenous European inhabitants. These peoples were systematically preyed upon and turned into slaves, acquired by Barbary pirates during slave raids on ships and by raids on coastal towns from Italy to the Netherlands, as far north as Iceland and in the eastern shores of the Mediterranean.”

“White slavery, white slave trade, and white slave traffic refer to the chattel slavery of White Europeans by non-Europeans (such as North Africans and the Muslim world), as well as by Europeans themselves, such as the Viking thralls or European Galley slaves. From Antiquity, European slaves were common during the reign of Ancient Rome and were prominent during the Ottoman Empire into the early modern period. In Feudalism, there were various forms of status below the Freeman that is known as Serfdom (such as the bordar, villein, vagabond and slave) which could be bought and sold as property and were subject to labor and branding by their owners or demense. Under Muslim rule, the Arab slave trades that included Caucasian captives were often fueled by raids into European territories or were taken as children in the form of a blood tax from the families of citizens of conquered territories to serve the empire for a variety of functions. In the mid-19th century, the term ‘white slavery’ was used to describe the Christian slaves that were sold into the Barbary slave trade.”

See also:

COLUMBUS, Ohio – A new study suggests that a million or more European Christians were enslaved by Muslims in North Africa between 1530 and 1780 – a far greater number than had ever been estimated before.

In a new book, Robert Davis, professor of history at Ohio State University, developed a unique methodology to calculate the number of white Christians who were enslaved along Africa’s Barbary Coast, arriving at much higher slave population estimates than any previous studies had found.

Most other accounts of slavery along the Barbary coast didn’t try to estimate the number of slaves, or only looked at the number of slaves in particular cities, Davis said. Most previously estimated slave counts have thus tended to be in the thousands, or at most in the tens of thousands. Davis, by contrast, has calculated that between 1 million and 1.25 million European Christians were captured and forced to work in North Africa from the 16th to 18th centuries.

Davis’s new estimates appear in the book Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast, and Italy, 1500-1800 (Palgrave Macmillan).

“Enslavement was a very real possibility for anyone who traveled in the Mediterranean, or who lived along the shores in places like Italy, France, Spain and Portugal, and even as far north as England and Iceland.”

“Much of what has been written gives the impression that there were not many slaves and minimizes the impact that slavery had on Europe,” Davis said. “Most accounts only look at slavery in one place, or only for a short period of time. But when you take a broader, longer view, the massive scope of this slavery and its powerful impact become clear.”

Davis said it is useful to compare this Mediterranean slavery to the Atlantic slave trade that brought black Africans to the Americas. Over the course of four centuries, the Atlantic slave trade was much larger – about 10 to 12 million black Africans were brought to the Americas. But from 1500 to 1650, when trans-Atlantic slaving was still in its infancy, more white Christian slaves were probably taken to Barbary than black African slaves to the Americas, according to Davis.

“One of the things that both the public and many scholars have tended to take as given is that slavery was always racial in nature – that only blacks have been slaves. But that is not true,” Davis said. “We cannot think of slavery as something that only white people did to black people.”

During the time period Davis studied, it was religion and ethnicity, as much as race, that determined who became slaves.

“Enslavement was a very real possibility for anyone who traveled in the Mediterranean, or who lived along the shores in places like Italy, France, Spain and Portugal, and even as far north as England and Iceland,” he said.

Pirates (called corsairs) from cities along the Barbary Coast in north Africa – cities such as Tunis and Algiers – would raid ships in the Mediterranean and Atlantic, as well as seaside villages to capture men, women and children. The impact of these attacks were devastating – France, England, and Spain each lost thousands of ships, and long stretches of the Spanish and Italian coasts were almost completely abandoned by their inhabitants. At its peak, the destruction and depopulation of some areas probably exceeded what European slavers would later inflict on the African interior.

Although hundreds of thousands of Christian slaves were taken from Mediterranean countries, Davis noted, the effects of Muslim slave raids was felt much further away: it appears, for example, that through most of the 17th century the English lost at least 400 sailors a year to the slavers.

Even Americans were not immune. For example, one American slave reported that 130 other American seamen had been enslaved by the Algerians in the Mediterranean and Atlantic just between 1785 and 1793.

Davis said the vast scope of slavery in North Africa has been ignored and minimized, in large part because it is on no one’s agenda to discuss what happened.

The enslavement of Europeans doesn’t fit the general theme of European world conquest and colonialism that is central to scholarship on the early modern era, he said. Many of the countries that were victims of slavery, such as France and Spain, would later conquer and colonize the areas of North Africa where their citizens were once held as slaves. Maybe because of this history, Western scholars have thought of the Europeans primarily as “evil colonialists” and not as the victims they sometimes were, Davis said.

Davis said another reason that Mediterranean slavery has been ignored or minimized has been that there have not been good estimates of the total number of people enslaved. People of the time – both Europeans and the Barbary Coast slave owners – did not keep detailed, trustworthy records of the number of slaves. In contrast, there are extensive records that document the number of Africans brought to the Americas as slaves.

So Davis developed a new methodology to come up with reasonable estimates of the number of slaves along the Barbary Coast. Davis found the best records available indicating how many slaves were at a particular location at a single time. He then estimated how many new slaves it would take to replace slaves as they died, escaped or were ransomed.

“The only way I could come up with hard numbers is to turn the whole problem upside down – figure out how many slaves they would have to capture to maintain a certain level,” he said. “It is not the best way to make population estimates, but it is the only way with the limited records available.”

Putting together such sources of attrition as deaths, escapes, ransomings, and conversions, Davis calculated that about one-fourth of slaves had to be replaced each year to keep the slave population stable, as it apparently was between 1580 and 1680. That meant about 8,500 new slaves had to be captured each year. Overall, this suggests nearly a million slaves would have been taken captive during this period. Using the same methodology, Davis has estimated as many as 475,000 additional slaves were taken in the previous and following centuries.

The result is that between 1530 and 1780 there were almost certainly 1 million and quite possibly as many as 1.25 million white, European Christians enslaved by the Muslims of the Barbary Coast.

Davis said his research into the treatment of these slaves suggests that, for most of them, their lives were every bit as difficult as that of slaves in America.

“As far as daily living conditions, the Mediterranean slaves certainly didn’t have it better,” he said.

While African slaves did grueling labor on sugar and cotton plantations in the Americas, European Christian slaves were often worked just as hard and as lethally – in quarries, in heavy construction, and above all rowing the corsair galleys themselves.

Davis said his findings suggest that this invisible slavery of European Christians deserves more attention from scholars.

“We have lost the sense of how large enslavement could loom for those who lived around the Mediterranean and the threat they were under,” he said. “Slaves were still slaves, whether they are black or white, and whether they suffered in America or North Africa.”

See Also: White Cargo by Don Jordan and Michael Walsh, New York University Press, 2007…READ MORE